When Daniel Stone was a child, he was the only white boy in a native Eskimo village where his mother taught, and he was teased mercilessly because he was different. He fought back, the baddest of the bad kids: stealing, drinking, robbing and cheating his way out of the Alaskan bush – where he honed his artistic talent, fell in love with a girl and got her pregnant. To become part of a family, he reinvented himself – jettisoning all that anger to become a docile, devoted husband and father. …more

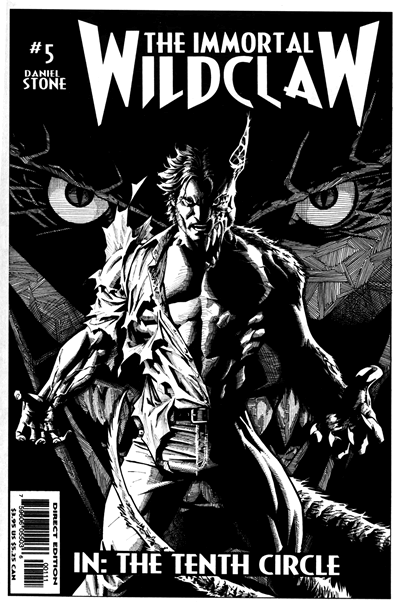

This book will take your breath away…(Picoult's) imagery is thick with ravens and blizzards and other wild things, plus she wisely parallels the Stones' saga with pages from Daniel's latest comic-in-progress (drawn in real life by Dustin Weaver): the story of a man who must rescue his daughter from hell. This book lands, as Picoult might say, like a fat black crow on your chest. Grade: A.”

The story behind The Tenth Circle

Spoiler alert – don’t read this answer if you haven’t read the book!!!

Jodi Picoult offers her most powerful chronicle yet as she explores the unbreakable bond between parent and child, and questions whether you can reinvent yourself in the course of a lifetime -- or if your mistakes are carried forever.

artwork by Dustin Weaver

Fifteen years later, when we meet Daniel again, he is a comic book artist. His wife teaches Dante’s Inferno at a local college; his daughter, Trixie, is the light of his life – and a girl who only knows her father as the even-tempered, mild-mannered man he has been her whole life. Until, that is, she is date raped…and Daniel finds himself struggling, again, with a powerlessness and a rage that may not just swallow him whole, but destroy his family and his future.

The publisher: Atria Books , 2006. (Book 13 )

When the hardcover of Tenth Circle was released in 2006, it debuted at #2 on the NY Times bestseller list, and was ranked #1 on the Wall Street Journal and Publisher's Weekly bestseller lists.

Not really. Although, at first glance, it looks a little different…the truth is that this novel, like so many of my others, explore the connections between a parent and a child, and revisit the theme of whether we really ever know anyone as well as we think we do. I like to think of it as Picoult-Plus: in addition to giving book clubs and buddies plenty to debate, you get another venue through which to unravel those issues – the artwork.

I started with Dante’s Inferno. I’d read it in college, and didn’t really like it, so I decided to give it another chance. Well, to be honest, I still don’t like it…but I’m mature enough now to appreciate some of his timeless themes – such as how the punishment fits the crime, and how you should be careful what you wish for…lest it come true. The worst thing you can do, according to Dante, is betray someone close to you – which fit very well with the story I was trying to tell in The Tenth Circle .

I went from reading Dante to reading comic books – because I knew my main character was going to be a comic book penciller. Having never been a 13-year-old boy, this genre was new to me…and not only did I immerse myself in actual comic, I also studied their history. The origin of modern comics traces back to two young Jewish men who couldn’t get newspaper jobs during the Depression. Schuster and Seigel instead imagined a world where the loser got the pretty girl and saved the world to boot – and their hero, Superman, greatly appealed to a country that desperately needed a hero. Superheroes evolved – all good guys in tights – until the 1960s when Marvel introduced Spiderman. He wasn’t a willing hero; he was moody and angry and resentful and lot like the teens who were reading him. Now, heroes have grown even more complex – Alan Moore’s and Neil Gaiman’s works spotlight heroes who don’t always win; who enjoy inflicting pain. I spent a great deal of time with my 12 year old son, Jake, our resident comic book expert, who immersed me in his favorite storylines. The more I learned, the more I realized that the epic poem and the comic book genre have a lot more in common than you’d think, since they both view a man’s life as the struggle between good and evil; they both address the vast gap between whom we pretend we are and whom we truly are.

I knew that Daniel’s struggle, in the book, was going to be precipitated by his daughter’s date rape…which led me to sit down a group of teenage girls and interview them, quite candidly, about sex and dating today. Now, I’ve done this before – for The Pact , for Salem Falls – but more than once during this conversation I found myself absolutely stunned. Instead of relationships, kids have random hookups, or friends with benefits – sexual experiences that they pretend never happened the next day. Oral sex isn’t considered sex. At parties, you’ll see games like Stoneface and Rainbow – which involve a boy with multiple sex partners, or a girl servicing several guys. The biggest reason to have sex in the first place is to get it over with; the pressure doesn’t come from boys, but from within the girl herself – you don’t want your girlfriends to find out you’re not doing the same things they are. And perhaps most upsetting – the girls told me that they feel empowered, because they’re the ones deciding whether or not to do these things. They pretend it doesn’t hurt when they’re not valued by the boys they “hook up” with; but then told me stories about cutting themselves with razor blades when the one night stand didn’t materialize into something more lasting. It was clear to me that we’re turning out a generation of kids who don’t know how to have a relationship with someone. We’re sending young men to college, who expect to get what they want when they want it (which supports the growing percentage of date rapes on campuses). We’re seeing high school girls who don’t even realize that what they’re “choosing” to do objectifies them, and strips them of any self-esteem. When I’ve gone to high schools to speak to students and I mention this research, the looks I get from the student audience are priceless – their jaws drop, because a) I know about it and b) I’m brave enough to tell them I know. Believe me, parents are not sitting around dinner tables talking about this – and this made me think of The Pact . Teen suicide, like teen sexuality, is an issue parents would rather not discuss with their kids, fearing that if they bring it up they might plant ideas in their child’s mind. But the sad truth is that it’s happening whether or not we want to talk to our kids about it…and based on my research for this book, it’s something we need to start talking about in earnest. Now.

The last bit of research I did – and the most fun – involved going to the Alaskan bush in the middle of winter, so that I could see through Daniel’s eyes. The airline reservation clerk laughed when I told her where I wanted to go in January – ultimately, I had to take a cargo plane from Anchorage to Bethel, with a load of sled dogs. It was -40 degrees Fahrenheit when I arrived, and I wore everything in my luggage at once and still had to borrow clothes. First, I helped out at the K300, a sled dog race, just like Trixie (you know you’ve arrived in Alaska when a lady musher grabs your arm and asks you to hold up a feed bag so that she can drop trou and pee). Then I headed to a Yup’ik Eskimo village. The villages are north of Bethel, and the only way to get there in January is to take a snowmobile up the frozen river (which, in the winter, actually gets its own highway number). Akiak is a village of 300, with no running water. My host was a Yup’ik Eskimo named Moses Owen. As I walked into his house, I tripped over a moose hoof in the Arctic entryway. I brought him oranges; he gave me dried fish. There are, of course, no toilets – just “honeybuckets” – a misnomer if ever there was one. Moses’ wife had her grandchild on her knee, and he kept pointing at me and laughing. She explained that he’d never seen anyone with my color hair before. In fact, Moses said, when the first whites came to the Alaskan bush, they were so pale that the Eskimos thought they were ghosts.

Moses explained to me that in his world, there’s a fluidity between the animal world and the human one. At any moment, a person might turn into an animal, or vice-versa. They also believe that words have remarkable power and that thought is equally as important as action – just because a word isn’t said out loud doesn’t mean its intention isn’t received. For example, if you go hunting and you’re thinking of elk, you’ll never catch one…because it can hear you. You must think of anything but the elk. Likewise, it would be downright rude to change someone’s mind by putting your own words into it. So you might say to a friend, “Tomorrow’s a good day to hunt.” It will be up to your buddy to understand that you’re actually inviting him along. To a Yup’ik Eskimo, then, silence is an act. Words are a weapon. And you don’t have to speak a wish for it to come true. Imagine, then, a case of date rape. Legally it always comes down to whether or not the girl said no. But to someone who’d grown up among the Yup’ik Eskimos – like Daniel Stone -- it wouldn’t have mattered if Trixie said it…or merely thought it.

A lot of people have been reevaluating the way they read a story, which I just love, because that’s part of the reason why I wrote the book. Some people want to absorb the art just where it is, mid-narrative. Some read the graphic novel first. Some save it for last. Most people are entranced by the way the art is just art until the narrative is added to it, almost as if there’s a chemical reaction…resulting in insight into Daniel’s character. Oh, and they seem to be having a good time searching for the hidden message in the art.

Parents who’ve read the book keep pulling me aside to desperately ask, “That teen sex stuff; the parties…that’s all fiction, right?” I think that peeling back the surface layer of what teenagers are really doing intimately with each other is startling for adults to blatantly see and hear – I anticipated that reaction. What took me by surprise, however, are the number of young women who’ve written to me to say that they were date raped, and never told anyone, because they were sure it was their fault in some way – they hadn’t expressed NO clearly enough. I think Trixie’s experience mirrors theirs, and validates their feelings – which allows them to open up about something they’ve hidden for years. Things like this are humbling -- when you write fiction you don’t expect to make a profound difference in someone’s real life.

I’d like to believe that I’m usually a better parent than any of my characters! However, a lot of The Tenth Circle grew out of watching my husband and my daughter, Sammy – they have a really special bond, because she’s the only girl, and she’s our youngest. Tim’s always said that he will continue to lift weights so that he can always carry her – and I’m sure he’s had his fantasies about not letting her date until she’s forty. Sammy’s only ten right now, but our oldest son, Kyle, is fourteen, and it’s interesting to see how much he’s changed in the past year. I think it’s always hard to watch your children take those fledgling steps into adulthood – in part because you know they’re going to stumble, and in part because you know they won’t want you to catch them when it happens (that’s the whole point of growing up). But does knowing all this make it any easier when it happens, for real? No way.

I have always said that I write books about questions that don’t have easy answers. If I had the answers, believe me, I’d be a lot richer and smarter. Since I don’t, I don’t think I have any right to tell a reader what’s the “right way” to think. To this end it’s really important to me to put all the different points of view of a situation into a book. Is it emotionally taxing? Sure – but second guessing oneself always is!

When I started this book, I was thinking of all the different ways we can tell stories – particularly the ones we tell ourselves, when we don’t want to admit the truth. I was also thinking of Dante’s Inferno , and that theme of being careful what you wish for. And I was intrigued by the thought of a main character who wasn’t good with words – an enigma you’d have to learn about through some other means. I began to wonder if there was a way to tell a story with different layers – so that they’d stand on their own, but when read together, would make each of the stories richer. There are, of course, hundreds of artistic forms for storytelling - opera, ballet, film, photography – but something about Dante kept pulling me back to the idea of a graphic novel. His levels of Hell seemed perfect for the genre. And conversely, a man who was struggling to deal with the emotional aftermath of his daughter’s rape might easily invent a character who was, metaphorically, doing the same thing. That’s how Wildclaw was born – the alter-ego of a man whose daughter is kidnapped by the Devil, so that her father, Duncan, literally has to go through Hell to get her back. I think as you read the graphic novel – particularly the circles where you see adulterers, and the Devil – you understand the psyche of its “creator” – Daniel. You see the same lake of ice he grew up with in the Alaskan bush represented, now, in art form to freeze the Devil up to his waist. You see the shapeshifting between human and animal form, like the Yup’ik Eskimos believe. Duncan’s fear that the animal parts of him will eclipse the human side mirror Daniel’s unspoken worry that the man he becomes in the aftermath of Trixie’s rape will be someone she does not recognize.

I didn’t feel like I was doing anything remarkably different – after all, all fiction used to be illustrated. And we know that graphic novels have enjoyed critical and commercial success recently. It’s just that I had the right story in which to bring them together with narrative fiction.

Unfortunately, I can’t draw comic books. Fortunately, I knew someone who could. When I was at Princeton, the guy who lived across the hall from me used to spend hours at his drafting table doing just that – and now, Jim Lee is one of the most famous artists in the industry. I got in touch with Jim, told him what I wanted to do, and asked him if he’d be able to find me an artist. He put me in touch with a young man named Dustin Weaver, who was an intern at Jim’s company. When Dustin agreed to help me out, we embarked on a collaboration that was really unlike anything I’d ever done. The narrative novel and the graphic novel were produced simultaneously. I would write him the script for the comic book – on screenwriting software – and then I’d get a few drawn pages back via email. Every now and then Dustin would ask me if I had any thoughts about what a character should look like – (for example, the Devil…I said he should think of Jack Nicholson, and I’ll be damned if the art didn’t turn out just that way). I also admit to falling just a little bit in love with the character of Duncan. Luckily, my husband doesn’t find pen-and-ink men a real threat.

We had a discussion about this in the car on the way to school today, because it’s such a good question. My daughter chose flight. My oldest son wants the ability to make anything out of thin air – like a million bucks, no doubt. My middle son, the comic book aficionado, said he’d rather have the power to take on other people’s powers, like Rogue. Me, well, I’m torn. As fabulous as teleportation would be (a la Nightcrawler) particularly during a book tour, I’d probably rather have a combination of telempathy and mind control – the ability to change people’s thoughts and feelings. But, of course, I don’t have superpowers…so instead I write novels and try to do that the old fashioned way.

I’m not; I don’t have nearly enough time to read something with anything approximating regularity. However, I have gone to multiple book clubs or done phone chats with those who are discussing my books. It’s always really nice – I mean, there are a lot of books in the world, and they chose mine ! For the most part, people are very complimentary – although I’m not quite sure if that’s because my books are really good, or because no one has the heart to tell me when I’m sitting right there that they’re not . I am always impressed by those people who are brave enough to say to my face, “I really didn’t like this part.” The good thing, though, is that I get to have the last word, and explain why I wrote it that way!

The best part of being a writer is meeting my fans. It never fails to amaze me that the people reading my books are no longer just friends of my mother or related to me distantly! I love knowing that I keep you up late at night and that you don’t get your housework done and that you hide my books behind your school textbooks because you can’t stop reading. I like meeting fans by stealth too – like yesterday, when a girl pulled one of my novels out of her purse at a restaurant, and I went over to ask her if she liked it…and then admitted that I’d written it (of course, if she’d hated the book, I would never have taken credit!)

“[This] novel's twists and suspense will satisfy the most adrenaline-addicted reader…Picoult must have set her keyboard on fire as she wrote. The energy and tumble-down acceleration is extraordinary.”

— Midwest Book Review

“A compelling read…Picoult is the women's fiction equivalent of Jerry Bruckheimer, and The Tenth Circle has 11th-hour plot twists reminiscent of a CSI episode…engrossing entertainment.”

— Globe & Mail review, Toronto

“Novels and comic books exhibit many differences. But in Jodi Picoult’s “The Tenth Circle,” the reader witnesses a marriage of the two - and it’s a marriage made in heaven...”The Tenth Circle” is strong enough as only a novel. But when coupled with its illustrated counterpart, it becomes a treat for both the mind and the eye.”

— Book Review, AP News Wire

“Picoult takes two hard-hitting subjects - rape and murder - and pulls them apart with such intelligence and insight that you'll never see them as clear-cut issues again. Tender, compelling and brilliant.”

— EVE Magazine, United Kingdom

“This is the kind of book that Book Clubs will be clamoring after for years to come and could form the basis for an unforgettable film.”

— The Brown Bookloft

“The Tenth Circle is absolutely the thought-provoking and topical novel readers have come to expect. What comes as a surprise is just how thoroughly the book twists the reader's heart…Picoult does a bang-up job on the narrative approach she's known for. She leads readers to consider thorny issues around motives and consequences.”

— Denver Post

“As she is known for in her writing, Picoult skillfully twists and turns this story in so many ways, keeping readers wondering how things will turn out until nearly the last, satisfying page.”

— Orlando Sentinel

“Picoult spins fast-paced tales of family dysfunction, betrayal, and redemption… (her) depiction of of these rites of contemporary adolescence is exceptional: unflinching, unjudgmental, utterly chilling. ”

— The Washington Post

“Another gripping, nuanced tale of a family in crisis from bestseller Picoult.”

— PEOPLE

“Jodi Picoult — here's a name almost guaranteed to make booksellers drool. She's an award-winning, bestselling author and a book clubber's dream: each of her twelve novels is meaty, engrossing, and tackles interesting situations or morally complex conundrums with enough twists and turns to keep the most jaded reader engrossed. And if all this weren't enough, she's profitably prolific as well: she cranks out a new book every year, like clockwork. She's also a very attractive woman who's charming and engaging, a publicists' dream, and every new book sets the Simon & Schuster marketing machines on full-throttle. Picoult is quite the tour de force… THE TENTH CIRCLE manages to remain vintage Picoult while demonstrating the author's clear development as a writer — her novel proves that she's willing to take chances, not only through the incorporation of graphic novel elements, but through her unique way of tackling resolutions. Strip away all of the marketing and publicist trappings behind this author's name, and what you'll find is a well-crafted novel and a smart writer who's not afraid to try something different and go out on a limb.”

— Bookreporter.com

“Some of Picoult's best storytelling distinguishes her twisting, metaphor-rich 13th novel (after Vanishing Acts ) about parental vigilance gone haywire, inner demons and the emotional risks of relationships …This story of a flawed family on the brink of destruction grips from start to finish.”

— Publishers Weekly, Starred Review

“Jodi Picoult's books explore all the shades of gray in a world too often judged in black and white. She does it again in The Tenth Circle ”

— The St. Louis Post-Dispatch

“When it comes to the freeze-frame of a family caught in the headlights of loss and irreversible regret, Picoult has no equal.”

— Jacquelyn Mitchard

“When a comic book artist married to a Dante scholar writes a graphic novel, what better title than The Tenth Circle? Picoult's latest novel actually features artwork in a tale that parallels his real life, and readers are drawn into the mystery. What truths will be revealed? And who, ultimately, will find justice? Picoult had this reader up until the very end of this fast-paced tale.”

— Library Journal

“There are no black and whites in Picoult's latest novel, except for the drawings that graphic artist Daniel Stone inks… Picoult's sad, complex novel should appeal to the many readers who have enjoyed her previous works.”

— Booklist

Laura Stone knew exactly how to go to Hell.

She could map out its geography on napkins at departmental cocktail parties; she was able to recite all of the passageways and rivers and folds by heart; she was on a first-name basis with its sinners. As one of the top Dante scholars in the country, she taught a course in this very subject; and had done so every year since being tenured at Monroe College. English 364 was also listed in the course handbook as Burn Baby Burn (or: What the Devil is the Inferno?), and was one of the most popular courses on campus in the second trimester even though Dante’s epic poem – the Divine Comedy – wasn’t funny at all.

Like her husband Daniel’s artwork, which was neither comic nor a book, the Inferno covered every genre of pop culture: romance, horror, mystery, crime. And like all of the best stories, it had at its center an ordinary, everyday hero who simply didn’t know how he’d ever become one.

Of the three parts of Dante’s masterpiece, the Inferno was Laura’s favorite to teach – who better to think about the nature of actions and their consequences than teeangers? The story was simple: over the course of three days – Good Friday to Easter Sunday – Dante trekked through the nine levels of Hell, each filled with sinners worse than the next, until finally he came through the other side. The poem was full of ranting and weeping and demons, of fighting lovers and traitors eating the brains of their victims – in other words, graphic enough to hold the interest of today’s college students…and to provide a distraction from her real life.

She regarded the students packing the rows in the utterly silent lecture hall. “Don’t move,” she instructed. “Not even a twitch.” Beside her, on the podium, an egg timer ticked away one full minute. She hid a smile as she watched the undergrads – all of whom suddenly had gotten the urge to sneeze or scratch their heads or wriggle. Finally, the timer buzzed, and the entire class exhaled in unison. “Well?” Laura asked. “How did that feel?”

“Endless,” a student called out.

“Anyone want to guess how long I timed you for?”

There was speculation: Two minutes. Five.

“Try sixty seconds,” Laura said. “Now imagine what it would be like to be encased in ice for eternity. Imagine that the slightest movement would freeze the tears on your face and the water surrounding you. God, as Dante saw Him, was all motion and energy – so the ultimate punishment for Lucifer is to not be able to move at all in his lake of ice. No fire, no brimstone – just the utter inability to take action.”

That – at its heart – was why Laura loved this poem…and why, right now, she felt so viscerally connected to it. Sure, it could be seen as a study of religion, or politics. Certainly it was a narrative of redemption. But when you stripped it down, this poem was the story of an ordinary guy in the throes of a midlife crisis.

Not unlike Laura herself. · · · · · ·

As Daniel Stone waited in the long queue of cars pulling up to the high school, he glanced at the stranger in the seat beside him and tried to remember when she used to be his daughter.

“Traffic’s bad today,” he said to Trixie, just to fill up the space between them.

Trixie didn’t respond. She fiddled with the radio, running through a symphony of static and song bites before punching it off entirely. Her red hair fell like a gash over her shoulder; her hands were burrowed in the sleeves of her North Face jacket. She turned to stare out the window, lost in a thousand thoughts, not a single one of which Daniel could guess.

These days it seemed like the words between them were only there to better outline the silences. Daniel understood better than anyone else that, in the blink of an eye, you might reinvent yourself. He understood that the person you were yesterday might not be the person you are tomorrow. But this time, he was the one who wanted to hold onto what he had, instead of letting go.

“Dad,” she said, and she flicked her eyes ahead, where the car in front of them was moving forward.

It was a complete cliché, but Daniel had assumed that the traditional distance that came between teenagers and their parents would pass by him and Trixie. They had a different relationship, after all; closer than most daughters and their fathers, simply because he was the one she came home to every day. He had done his due diligence in her bathroom medicine cabinet and her desk drawers and underneath her mattress – there were no drugs, no accordion-pleated condoms. Trixie was just growing away from him, and somehow that was even worse.

This September – and here was another cliché – Trixie had gotten a boyfriend. Daniel had had his share of fantasies: how he’d be casually cleaning a pistol when she was picked up for her first date; how he’d buy a chastity belt on the Internet. In none of those scenarios, though, had he ever really considered how the sight of a boy with his proprietary hand around his daughter’s waist might make him want to run until his lungs burst. And in none of these scenarios had he seen Trixie’s face fill with light when he came to the door, the same way she’d once looked at Daniel. Overnight, the little girl who vamped for his home videos now moved like a vixen when she wasn’t even trying. Overnight, his daughter’s actions and habits stopped being cute, and started being something terrifying.

His wife reminded him that the tighter he kept Trixie on a leash, the more she’d fight the chokehold. After all, Laura pointed out, rebelling against the system was what led her to start dating Daniel. So when Trixie and Jason went out to a movie, Daniel forced himself to wish her a good time. When she escaped to her room to talk to her boyfriend privately on the phone, he did not hover at the door. He gave her breathing space; and somehow, that had become an immeasurable distance.

“Hello?!” Trixie said, snapping Daniel out of his reverie. The cars in front of them had pulled away; the crossing guard was furiously miming to get Daniel to drive up.

“Well,” he said. “Finally.”

Trixie pulled at the door handle. “Can you let me out?”

Daniel fumbled with the power locks. “I’ll see you at three,” he said.

“I don’t need to be picked up.”

Daniel tried to paste a wide smile on his face. “Jason driving you home?”

Trixie gathered together her backpack and jacket. “Yeah,” she said. “Jason.” She slammed the truck door and blended into the mass of teenagers funneling toward the front door of the high school.

“Trixie!” Daniel called out the window, so loud that several other kids turned around with her. Trixie’s hand was curled into a fist against her chest, as if she was holding tight to a secret. She looked at him, waiting.

There was a game they had played when Trixie was little, and would pore over the comic book collections he kept in his studio for research when he was drawing. Best transportation? she’d challenge, and Daniel would say the Batmobile. No way, Trixie had said. Wonder Woman’s invisible plane.

Best costume?

Wolverine, Daniel said; but Trixie voted for the Dark Phoenix.

Now, he leaned toward her. “Best superpower?” he asked.

It had been the only answer they agreed upon: Flight. But this time, Trixie looked at him as if he were crazy to be bringing up a stupid game from a thousand years ago. “I’m going to be late,” she said, and she started to walk away.

Cars honked, but Daniel didn’t put the truck into gear. He closed his eyes, trying to remember what he had been like at her age. At fourteen, Daniel had been living in a different world, and doing everything he could to fight, lie, cheat, steal, and brawl his way out of it. At fourteen, he had been someone Trixie had never seen her father be. Daniel had made sure of it.

“Daddy.”

Daniel turned to find Trixie standing beside his truck. She curled her hands around the lip of the open window; the glitter in her pink nailpolish catching the sun. “Invisibility,” she said, and then she melted into the crowd behind her. · · · · · ·

Trixie Stone had been a ghost for fourteen days, seven hours, and thirty-six minutes now, not that she was officially counting. This meant that she walked around school and smiled when she was supposed to; she pretended to listen when the algebra teacher talked about commutative properties; she even sat in the cafeteria with the other ninth graders. But while they laughed at the lunch ladies’ hairstyles (or lack thereof), Trixie studied her hands and wondered whether anyone else noticed that if the sun hit your palm a certain way, you could see right through the skin, to the busy tunnels with blood moving around inside. Corpuscles. She slipped the word into her mouth and tucked it high against her cheek like a sucking candy, so that if anyone happened to ask her a question she could just shake her head, unable to speak.

Kids who knew (and who didn’t? the news had traveled like a forest fire) were waiting to see her lose her careful balance. Trixie had even overheard one girl making a bet about when she might fall apart in a public situation. High school students were cannibals; they fed off your broken heart while you watched, and then shrugged and offered you a bloody, apologetic smile.

Visine helped. So did Preparation H under the eyes, as disgusting as it was to imagine. Trixie would get up at 5:30 in the morning and carefully select a double-layer of long-sleeved t-shirts and a pair of flannel pants; gather her hair into a messy ponytail. It took an hour to make herself look like she’d just rolled out of bed; like she’d been losing no sleep at all over what had happened. These days, her entire life was about making people believe she was someone she wasn’t anymore.

Trixie crested the hallway on a sea of noise – lockers gnashing like teeth; guys yelling out afternoon plans over the heads of underclassmen; change being dug out of pockets for vending machines. She turned Trixie turned the corner and saw them: Jessica Ridgeley, with her long sweep of blonde hair and her dermatologist’s-daughter skin, was leaning against the door of the AV room kissing Jason.

He was wearing the faded denim shirt she’d borrowed once when he spilled Coke on her while they were studying; and his black hair was a mess. You need a part, she used to tell him, and he’d laugh. I’ve got better ones, he’d say.

She could smell him -- shampoo and peppermint gum and believe it or not, the cool white mist of utter ice. It was the same smell on the t-shirt she’d hidden in the bottom of her pajama drawer, the one he didn’t know she had, the one she wrapped around her pillow each night before she went to sleep. It kept the details in her dreams: a callus on the edge of Jason’s wrist, rubbed raw by his hockey glove. The flannel-covered sound of his voice when she called him on the phone and woke him. The way he would twirl a pencil around the fingers of one hand when he was nervous, or thinking too hard.

He was doing that, she remembered, when he broke up with her.

Trixie became a rock, the sea of students parting around her. She watched Jason’s hands slip into the back pockets of Jessica’s jeans. She could see the dimple on the left side of his mouth, the one that only appeared when he was speaking from the heart.

Was he telling Jessica that his favorite sound was the thump that laundry made when it was turning around in a dryer? That sometimes, he could walk by the telephone and think she was going to call, and sure enough she did? That once, when he was ten, he broke into a candy machine because he wanted to know what happened to the quarters once they went inside?

Was she even listening?

Suddenly, Trixie felt someone grab her arm and start dragging her down the hall, out the door and into the courtyard. She smelled the acrid twitch of a match, and a minute later, a cigarette had been stuck between her lips. “Inhale,” Zephyr commanded.

Zephyr Santorelli-Weinstein was Trixie’s oldest friend. She had enormous doe-eyes and olive skin and the coolest mother on the planet – one who bought her incense for her room and took her to get her navel pierced like it was an adolescent rite. She had a father, too, but he lived in California with his new family and Trixie knew better than to bring up the subject. “What class have you got next?”

“French.”

“Madame Wright is senile. Let’s ditch.”

Bethel High had an open campus, not because the administration was such a fervent promoter of teen freedom, but because there was simply nowhere to go. Trixie walked beside Zephyr along the access road to the school, their faces ducked against the wind; their hands stuffed into the pockets of their North Face jackets. The criss-cross pattern where she’d cut herself an hour earlier on her arm wasn’t bleeding anymore, but the cold made it sting. Trixie automatically started breathing through her mouth, because even from a distance, she could smell the gassy, rotten-egg odor from the paper mill to the north that employed most of the adults in Bethel. “I heard what happened in Psych,” Zephyr said.

“Great,” Trixie muttered. “Now the whole world thinks I’m a loser and a freak.”

Zephyr took the cigarette from Trixie’s hand and smoked the last of it. “What do you care what the whole world thinks?”

“Not the whole world,” Trixie admitted. She felt her eyes prickle with tears again, and she wiped her mitten across them. “I want to kill Jessica Ridgeley.”

“If I were you, I’d want to kill Jason,” Zephyr said. “Why do you let it get to you?”

Trixie shook her head. “I’m the one who’s supposed to be with him, Zephyr. I just know it.”

They had reached the turn of the river past the park-and-ride, where the bridge stretched over the Androscoggin River. This time of year, it was nearly frozen over; with great swirling art sculptures that formed as ice built up around the rocks that crouched in the riverbed. If they kept walking another quarter-mile, they’d reach the town, which basically consisted of a Chinese restaurant, a minimart, a bank, a toy store, and a whole lot of nothing else.

Zephyr watched Trixie cry for a few minutes, then leaned against the railing of the bridge. “You want the good news or the bad news?”

Trixie blew her nose in an old tissue she’d found in her pocket. “Bad news.”

“Martyr,” Zephyr said, grinning. “The bad news is that my best friend has officially exceeded her two week grace period for mourning over a relationship, and that she will be penalized from here on in.”

At that, Trixie smiled a little. “What’s the good news?”

“Moss Minton and I have sort of been hanging out.”

Trixie felt another stab in her chest. Her best friend, and Jason’s?. “Really?”

“Well, maybe we weren’t actually hanging out. He waited for me after English class today to ask me if you were okay…but still, the way I figure it, he could have asked anyone, right?”

Trixie wiped her nose. “Great. I’m glad my misery is doing wonders for your love life.”

“Well, it’s sure as hell not doing anything for yours,” Zephyr said. “You can’t keep crying over Jason. He knows you’re obsessed.” She shook her head. “Guys don’t want high-maintenance, Trix. They want…Jessica Ridgeley.”

“What the fuck does he see in her?”

Zephyr shrugged. “Who knows. Bra size? Neanderthal IQ?” She pulled her messenger bag forward, so that it she could dig inside for a pack of M&Ms. Hanging from the edge of the bag were twenty linked pink paper clips.

Trixie knew girls who kept a record of sexual encounters in a journal, or by fastening safety pins to the tongue of a sneaker. For Zephyr, it was paper clips. “A guy can’t hurt you if you don’t let him,” Zephyr said, running her finger across the paper clips, so that they danced.

These days, having a boyfriend or a girlfriend was not in vogue; most kids trolled for random hookups. The sudden thought that Trixie might have been that to Jason made her feel sick to her stomach. “I can’t be like that.”

Zephyr ripped open the bag of candy and passed it to Trixie. “Friends with benefits. It’s what the guys want, Trix.”

“How about what the girls want?”

Zephyr shrugged. “Hey, I suck at algebra; I can’t sing on key; and I’m always the last one picked for a team in gym…but apparently I’m quite gifted when it comes to hooking up.”

Trixie turned, laughing. “They tell you that?”

“Sure,” Zephyr said. “Don’t knock it until you’ve tried it. You get all the fun, without any of the baggage. And the next day you just act like it never happened.”

Trixie tugged on the paper clip chain. “If you’re acting like it never happened, they why are you keeping track?”

“Once I hit a hundred, I can send away for the free decoder ring,” Zephyr joked “I don’t know. I guess it’s just so I remember where I started.”

Trixie opened her palm and surveyed the M&Ms. The food coloring dye was already starting to bleed against her skin. “Why do you think the commercials say they won’t melt in your hands, when they always do?”

“Because everyone lies,” Zephyr replied.

All teenagers knew this was true. The process of growing up was nothing more than figuring out what doors hadn’t yet been slammed in your face. For years, Trixie’s own parents had told her that she could be anything, have anything, do anything. That was why she’d been so eager to grow up – until she got to adolescence and slammed into a big, fat wall of reality. As it turned out, she couldn’t have anything she wanted. You didn’t get to be pretty or smart or popular just because you wanted it. You didn’t control your own destiny; you were too busy trying to fit in. Even now, as she stood here, there were a million parents setting their kids up for heartbreak.

Zephyr stared out over the railing. “This is the third time I’ve cut English this week.”

In French class, Trixie was missing a quiz on le subjonctif. Verbs, apparently, had moods too: they had to be conjugated a whole different way if they were used in clauses to express want, doubt, wishes, judgment. She had memorized the red-flag phrases last night: It is doubtful that. It’s not clear that. It seems that. It may be that. Even though. No matter what. Without.

She didn’t need a stupid leçon to teach her something she’d known for years: Given anything negative or uncertain, there were rules that had to be followed. · · · · · ·

“You have to do something pretty awful, to wind up in the bottom level of Hell,” Laura said, surveying her class. “So what did Lucifer do to tick God off?”

It had been a simple disagreement, Laura thought. Like almost every other rift between people, that’s how it started. “Well, one day God turned to his right-hand-man, Lucifer, and said that he was thinking of giving those cool little toys he created – namely, people – the right to choose how they acted. Free will. Lucifer thought that power should belong only to angels. He staged a little coup; and he lost big time.”

Laura started walking through the aisles – one of the caveats of free Internet access at the college was that kids used lecture hours to shop online and download porn, if the professor wasn’t vigilant. “What makes the Inferno so brilliant are the contrapassos – the punishments that fit the crime. In Dante’s mind, sinners pay in a way that reflects what they did wrong on earth. Lucifer didn’t want man to have choices; so he himself winds up paralyzed. Fortunetellers walk around with their heads on backward. Adulterers end up joined together for eternity, without getting any satisfaction from it.” Laura shook off the image that rose in her mind. “Apparently,” she joked, “the clinical trials for Viagra were done in Hell.”

Her class laughed as she headed toward her podium. “In the 1300s -- before Italians could tune into The Matrix or Star Wars or Lord of the Rings -- this poem was the ultimate battle of good versus evil,” she said. “I like the word evil. Scramble it a little, and you get vile, and live. Good, on the other hand, is just a command to go do.”

The four graduate students who would lead the class sections for this course were all sitting in the front row with their computers balanced on their knees. Well, three of them were. There was Alpha, the self-christened retro-feminist, which as far as Laura could tell meant that she gave a lot of speeches about how modern women had been driven so far from the home they no longer felt comfortable inside it. Beside her, Aine scrawled on the inside of one alabaster arm – most likely her own poetry. Naryan, who could type faster than Laura could breathe, looked up over his laptop at her, a crow poised for a crumb. Only Seth sprawled in his chair, his eyes closed; his long hair spilling over his face. Was he snoring?

She felt a flush rise up the back of her neck; and immediately tried to will it away. But physical responses didn’t always knuckle down to rational thought, Laura knew. She turned her back on Seth Dummerston and glanced up at the clock in the back of the lecture hall. “Read through the fifth canto,” Laura instructed. “Monday, we’ll be talking about poetic justice, versus divine retribution. Have a nice weekend, folks.”

The students gathered their backpacks and laptops, chattering about the bands that were playing near campus later on, and the B__ party that had brought in a truckload of real sand for Caribbean Night. They wound scarves around their necks like bright bandages and filed out of the lecture hall, already dismissing Laura’s class from their minds.

Laura didn’t need to prepare for her lecture Monday; she was living it. Be careful what you wish for, she thought. You just might get it.

Six months ago, she had been so sure that what she was doing was right – a liaison so natural that stopping it was more criminal than letting it flourish. When his hands roamed over her, she transformed: no longer Professor Laura Stone, but a woman who felt before she reasoned. But now, when Laura thought of what she had done, she wanted to blame a tumor, temporary insanity, anything but her own selfishness. Now, all she wanted was damage control: to break it off, to slip back into the seam of her family before they had a chance to realize how long she’d been missing.

When the lecture hall was empty, Laura turned off the overhead lights. She dug in her pocket for her office keys. Damn, had she left them in her computer bag?

“Veil.”

Laura turned around, already recognizing the soft Southern curves of Seth Dummerston’s voice. He stood up and stretched, unfolding his long body after that nap. “It’s another anagram for evil,” he said. “The things we hide.”

She stared at him coolly. “You fell asleep during my lecture.”

“I had a late night.”

“Whose fault is that?” Laura asked.

Seth stared at her the way she used to stare at him; then bent forward until his mouth brushed over hers. “You tell me,” he whispered. · · · · · ·

If he had the choice, Daniel would draw a villain every time.

There just wasn’t all that much you could do with a hero. They came with a set of traditional standards: square jaw, overdeveloped calves, perfect teeth. They stood half a foot taller than your average man. They were anatomical marvels, intricate displays of musculature. They sported ridiculous, knee-high boots that no one without superhuman strength would be caught dead wearing.

On the other hand, your average bad guy might have a face shaped like an onion, an anvil, a pancake. His eyes could bulge out or recess in the folds of his skin. His physique might be meaty or cadaverous; furry or rubberized or covered with lizard scales. He could speak in lightning; throw fire; swallow mountains. A villain let your creativity out of its cage.

The problem was: you couldn’t have one without the other. Good and evil were like all of those other bipolar terms that were defined by their opposite: light and dark, full and empty, rich and poor. There couldn’t be a bad guy unless there was a good guy to create the standard. And there couldn’t be a good guy until a bad guy showed just how far off the path he might stray.

Today Daniel sat hunched at his drafting table, procrastinating. He twirled his mechanical pencil; he kneaded an eraser in his palm. He was having a hell of a time turning his main character into a hawk. He had gotten the wingspan right, but he couldn’t seem to humanize a face behind the bright eyes and beak.

Daniel was a comic book penciller. While Laura had built up the academic credentials to land her a tenured position at Monroe College, he’d worked out of the home with Trixie at his feet as he drew filler chapters for DC Comics. His style got him noticed by Marvel, who asked him numerous times to come work in NYC on Ultimate X-Men – but Daniel put his family before his career. He did graphic art to pay the mortgage: logos and illustrations for corporate newsletters – until last year, just before his fortieth birthday, when Marvel signed him to work from home on a project all his own.

He kept a picture of Trixie over his workspace – not just because he loved her, but because for this particular comic – The Tenth Circle – she was his inspiration. Well, Trixie and Laura. Laura’s obsession with Dante had provided the bare bones plot of the story; Trixie had provided the impetus. But it was Daniel who was responsible for creating his main character – Wildclaw – a hero that this industry had never seen.

Historically, comics had been geared toward teenage boys. Daniel had come to Marvel with a different concept – a character designed for the demographic group of adults who had been weaned on comic books…yet who now had the spending power they’d lacked as adolescents. Adults who wanted sneakers endorsed by Michael Jordan and watched news programs that looked like MTV segments and played Tetris on GameBoy SPs during their business class flights. Adults who would immediately identify with Wildclaw’s alter ego, Duncan: a forty-year-old father who knew that getting old was hell; who wanted to keep his family safe; whose powers controlled him, instead of the other way around.

The narrative of the comic book followed Duncan, an ordinary father searching for his daughter, who had been stolen away into Dante’s levels of Hell. When provoked, through rage or fear, he’d morph into Wildclaw – literally becoming an animal. The catch was this: power always involved a loss of humanity – if Duncan turned into a hawk or a bear or a wolf to elude a dangerous creature, a piece of him would stay that way. His biggest fear was that if and when he did find his missing daughter, she would no longer recognize who he’d become in order to save her.

Daniel looked down at what he had on the page so far, and sighed. The problem wasn’t in drawing the hawk – he could do that in his sleep – it was in making sure the reader saw the human behind it. It was not new to have a hero who morphed into an animal – but, then, Daniel had come by it honestly. He’d grown up as the only white boy in a native Alaskan village where his mother was a schoolteacher. In Akiak, people spoke freely of children who went to live with seals; of men who shared a home with polar bears. One woman had married a dog and given birth to puppies, only to peel back the fur to see they were actually babies underneath. There was no firm line between man and animal -- an animal was simply a non-human person, with the same ability to make conscious decisions, and humanity simmered under their skins. You could see it in the way they sat together for meals, or fell in love, or grieved. And this went both ways: sometimes, in a human, there would turn out to be a hidden bit of a beast.

Daniel’s best and only friend in the village was a Yup’ik boy named Cane. Cane’s grandfather had taken it upon himself to teach the kas’saq how to hunt and fish and learn everything else that he would really need to know. For example, how after killing a rabbit, you had to be quiet, so that the animal’s spirit could visit. How at fish camp, you’d set the bones of the salmon free in the river, whispering Ataam taikina. Come back again.

Daniel spent most of his childhood waiting to leave. He was a kas’saq, a white kid; and this was reason enough to be teased or bullied or beaten. By the time he was Trixie’s age, he was getting drunk, damaging property, and making sure the rest of the world knew better than to fuck with him. But when he wasn’t doing those things, he was drawing – characters who, against all odds, fought and won. Characters that he hid in the margins of his schoolbooks and on the canvas of his bare palm. He drew to escape, and eventually, at age seventeen, he did.

Once Daniel left Akiak, he never looked back. He learned how to stop using his fists; how to put rage on the page instead. He got a foothold in the comics industry. He never talked about his life in Alaska; and Trixie and Laura knew better than to ask. He became a typical suburban father – one who coached soccer and grilled burgers and mowed the lawn – a man you’d never expect had been accused of something so awful, he’d tried to outrun himself.

Daniel squeezed the eraser he was kneading and completely rubbed out the hawk he’d been attempting to draw. Maybe if he started with the Duncan-the-man, instead of the Wildclaw-the-beast? He took his mechanical pencil and started sketching the loose ovals and scribbled joints that materialized into his unlikely hero. No spandex; no high boots, no half-mask: Duncan’s habitual costume was a battered jacket, jeans, and sarcasm. Like Daniel, Duncan had shaggy dark hair and a dark complexion. Like Daniel, Duncan had a teenage daughter. And like Daniel, everything Duncan did or didn’t do was linked to a past that he refused to discuss.

When you got right down to it, Daniel was secretly drawing himself.

· · · · · ·

Trixie wasn’t lying, not really. She had told her father she was going to her best friend Zephyr’s house, and she was. She did plan to sleep over.

But Zephyr’s mother had gone to visit her older brother at Wesleyan College for the weekend, and Trixie wasn’t the only one who’d been invited for the evening. A bunch of people had come, including some hockey players.

Like Jason.

Zephyr had laid out the guidelines for Trixie’s surefire success that night: First, look hot. Second, drink whenever, whatever. Third – and most importantly – do not break the Two-and-a-half Hour Rule. That much time had to pass at the party before Trixie was allowed to talk to Jason. In the meantime, Trixie had to flirt with everyone but him. According to Zephyr, Jason expected Trixie to still be pining for him. When the opposite happened -- when he saw other guys checking Trixie out and telling him he’d blown it -- it would shock him into realizing his mistake.

By now, the party had wound down. Only four people remained: Zephyr and Trixie, Jason, and his best friend Moss, another hockey player. They had been playing strip poker long enough for the stakes to be important. Jason had folded a while ago; he stood against the wall with his arms crossed, watching the rest of the game develop.

Zephyr laid out her cards with a flourish: two pairs -- threes, and jacks. On the couch across from her, Moss tipped his hand and grinned. “I have a straight.”

Zephyr had already taken off her shoes, her socks, and her pants. She stood up and started to peel off her shirt. She walked toward Moss in her bra, draping her t-shirt around his neck and then kissing him so slowly that all the pale skin on his face turned bright pink.

When she sat back down, she glanced at Trixie, as if to say, That’s how you do it.

“Stack the deck,” Moss said. “I want to see if she’s really a blonde.”

Zephyr turned to Trixie. “Stack the deck,” she said. “I want to see if he’s really a guy.”

“Hey, Trixie, what about you?” Moss asked.

Trixie’s head was cartwheeling, but she could feel Jason’s eyes on her. Maybe this was where she was supposed to go in for the kill. She looked to Zephyr, hoping for a cue, but Zephyr was too busy hanging on Moss to pay attention to her.

Oh my God, it was brilliant.

If the goal of this entire night had been to get Jason jealous, the surest way to do it would be to come on to his best friend.

Trixie stood up and tumbled right into Moss’s lap. His arms came around her, and her cards spilled onto the coffee table: the two of hearts, the six of diamonds, a queen of clubs, a three of clubs, and the eight of spades. Moss started to laugh. “Trixie, that’s the worst hand I’ve ever seen.”

“Yeah, Trix,” Zephyr said, staring. “You’re asking for it.”

Trixie glanced at her. She knew, didn’t she, that the only reason she was flirting with Moss was to make Jason jealous? But before she could telegraph this with some kind of E.S.P., Moss snapped her bra strap. “I think you lost,” he said, grinning, and he sat back to see what piece of clothing she was going to take off.

Trixie was down to her black bra and Ace bandage and her low rise jeans – the ones she was wearing without underwear. She wasn’t planning on parting with any of those items. But she had a plan – she was going to remove her earrings. She lifted her left hand up to the lobe, only to realize that she’d forgotten to put them on. The gold hoops were sitting on her dresser, in her bedroom, just where she’d left them.

Trixie had already removed her watch, and her necklace, and her barrette. She’d even cut off her macramé anklet. A flush rose up her shoulders – her bare shoulders – onto her face. “I fold.”

“You can’t fold after the game,” Moss said.

She swallowed hard and stood up. Flirting with other guys was one thing; being a total slut was another.

“Rules are rules,” Moss said.

Jason pushed away from the wall and walked closer. “Give her a break, Moss.”

“I think she’d rather have something else...”

“Leave me alone,” Trixie said, her voice skating the thin edge of panic. She held her hands crossed in front of herself. Her heart was pounding so hard she thought it would burst into her palm.

“I’ll pinch-strip for her,” Zephyr suggested, leaning into to Moss.

But at that moment, Trixie looked at Jason, and remembered why she had suggested this game in the first place. It’s worth it, she thought, if it brings him back. “I’ll do it,” she said. “But just for a second.”

Turning her back to the three of them, she slipped the straps of her bra down her arms and felt her breasts come free. She took a deep breath and spun around.

Jason was staring down at the floor. But Moss was holding up his cell phone, and before Trixie could understand why, he’d snapped a picture of her.

She fastened her bra and lunged for the phone. “Give me that!”

He stuffed it in his pants. “Come and get it, baby.”

Suddenly Trixie found herself being pulled off Moss. The sound of Jason’s fist hitting Moss over and over made her cringe. “Jesus Christ, lay off!” Moss cried. “I thought you said you were finished with her.”

Trixie grabbed for her blouse, wishing that it was something flannel or fleece that would completely obliterate her. She held it in front of her and ran into the bathroom down the hall. Zephyr followed her, coming into the tiny room and closing the door behind her.

Shaking, Trixie slipped her hands into the sleeves of the blouse. “Make them go home.”

“But it’s just getting interesting,” Zephyr said.

Trixie looked up, stunned. “What?”

“Well, for God’s sake, Trixie. So he had a camera phone, big fucking deal. It was a joke.”

“Why are you taking his side?”

“Why are you being such an asshole?”

Trixie felt her cheeks grow hot. “This was your idea. You told me that if I did what you said, I’d get Jason back.”

“Yeah,” Zephyr shot back. “So why were you all over Moss?”

Trixie thought of the paper clips on Zephyr’s backpack. Random hookups weren’t random, no matter what you told yourself. Or your best friend.

There was a knock on the door, and then Moss opened it. His lip was split, and he had a welt over his left eye. “Oh my God,” Zephyr said. “Look at what he did to you.”

Moss shrugged. “He’s done worse during a scrimmage.”

Zephyr threaded her fingers through his. “I think you need to lie down,” she said. “Preferably with me.” As she tugged Moss out of the bathroom and upstairs, she didn’t look back.

Trixie sat down on the lid of the toilet and buried her face in her hands. Distantly, she heard the music being turned off. Her temples throbbed, and her arm where she’d cut it earlier. Her throat was dry as leather. She reached for a half-empty can of Coke on the sink and drank it. She wanted to go home.

“Hey.”

Trixie glanced up to find Jason staring down at her. “I thought you left.”

“I wanted to make sure you were all right. You need a ride home?”

Trixie wiped her eyes, a smear of mascara coming off on the heel of her hand. She could only imagine how awful she looked right now. “That would be great,” she said; and then she began to cry.

He pulled her upright and into his arms. After tonight, after everything that had happened and how stupid she’d been, all she wanted was a place where she fit. Everything about Jason was right – from the temperature of his skin to the way that her pulse matched his. When she turned her face into the bow of his neck, she pressed her lips against his collarbone: not quite a kiss; not quite not one.

She thought, hard, about lifting her face up to his before she did it. She made herself remember what Moss had said: I thought you were done with her.

When Jason kissed her, he tasted of rum and of indecision. She kissed him back until the room spun, until she couldn’t remember how much time had passed. She wanted to stay like this forever. She wanted the world to grow up around them, a mound in the landscape where only violets bloomed, because that was what happened in a soil too rich for its own good.

Trixie rested her forehead against Jason’s. “I don’t have to go home just yet,” she said. · · · · · ·

Daniel was dreaming of Hell. There was a lake of ice, and a run of tundra. A dog tied to a steel rod, its nose buried in a dish of fish soup. There was a mound of melting snow, revealing candy wrappers, empty Pepsi cans, a broken toy. He heard the hollow thump of a basketball on the slick wooden boardwalk; and the tail of a green tarp rattling against the seat of the snowmachine it covered. He saw a moon that hung too late in the sky, like a drunk unwilling to leave the best seat at the bar.

At the sound of the crash, he came awake immediately to find himself still alone in bed. It was 4:32 AM – and Laura hadn’t come home. He walked into the hall, flipping light switches as he passed. “Laura,” he called again, “is that you?”

The hardwood floors felt cold beneath his bare feet. Nothing seemed to be out of the ordinary downstairs; yet by the time he reached the kitchen he had nearly convinced himself that he was about to come face to face with an intruder. An old wariness rose in him, a muscle memory of fight or flight that he’d thought he’d long forgotten.

There was no one in the cellar, or the half-bath, or the dining room. The telephone still slept on its cradle in the living room. It was in the mudroom that he realized Trixie must have come home early: her coat was here; her boots kicked off on the brick floor.

“Trixie?” he called out, heading upstairs again.

But she wasn’t in her bedroom, and when he reached the bathroom, the door was locked. Daniel rattled it, but there was no response. He threw his entire weight against the jamb until the door burst free.

Trixie was shivering, huddled in the crease made by the wall and the shower stall. “Baby,” he said, coming down on one knee. “Are you sick?” But then Trixie turned in slow-motion, as if he was the last person she’d ever expected to see. Her eyes were empty; ringed with mascara. She was wearing something black and sheer that was ripped at the shoulder. “Daddy,” she said, and she started to cry.

“Did something happen at Zephyr’s?”

Trixie nodded. She opened her mouth to speak, but then pressed her lips together; shaking her head.

“You can tell me,” Daniel said, gathering her into his arms as if she were small again.

Her hands were knotted together between them, like a heart that had broken its bounds. “Daddy,” she whispered. “He raped me.”